Excerpt from a digital artist’s journal, 2023:

“I code, I create, I disrupt. My work is not ‘pretty’—it is messy, glitchy, fragmented, just like the reality of women navigating a digital world that still seeks to erase us. If the system wasn’t made for us, then we will make our own.”

For centuries, the world of art has been a grand arena where men painted their versions of reality on the canvas of history, while women remained on the fringe—muses, not masters; subjects, not creators. Their fingers chiselled, drew, and danced in the face of invisibility, but their creations were dismissed as dainty, personal, or ornamental. What does it mean when a woman picks up the brush, the pen, the stage—not as ornament, but as a weapon of protest? Her solitude is not mythicised; it is unmediated. Her rage is not hysteria; it is revolution. And yet, even now, the world is reluctant to accept women’s art as universal.

The recovery of women’s artistic space has been at the heart of feminist critique, resisting systemic erasure and challenging women artists to be part of mainstream artistic histories. Linda Nochlin’s seminal essay Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? (1971) critically analysed the structural impediments—such as restricted education and institutional sexism—that historically excluded women from the art world. She contended that the absence of great women artists was not due to a lack of talent but the deeply entrenched patriarchal systems that constructed artistic legitimacy. Griselda Pollock expanded on this by employing a Marxist-feminist and psychoanalytic critique to dismantle the myth of the “universal artist,” exposing how cultural production has been constructed through gendered divisions of labour (Pollock, 1988).

Women’s artworks have long been relegated to the realm of “craft” or “domestic” art, described as decorative rather than intellectual or revolutionary. Textile arts, embroidery, and quilting— despite their complexity—were dismissed as mere handicrafts, in opposition to the “high art” of male-dominated painting and sculpture. Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party (1979)as shown in Figure 1used embroidery to elevate traditional women’s crafts into feminist statements, stretching the boundaries between domesticity and fine art. Even today, artists like Faith Ringgold, who uses quilting to narrate Black feminist histories, continue to challenge the “craft”/”art” binary, subverting these gendered hierarchies.

Figure 1: Banquet table placed on 999 handmade tiles

Source: Britannica

Performance as Protest: Reclaiming Public, Cultural and Cyberspace

The Nirbhaya street play, a one-person theatrical piece, was a blazing act of protest art, reclaiming streets as spaces of resistance. Staged in response to the 2012 Delhi gang rape, the performance takes the personal into the political, capturing the outrage and grief of women whose voices have long been silenced. By occupying streets, bazaars, and city corners—spaces that have historically been unsafe for women—the play turns the geometry of oppression on its head, turning the vulnerability of the female body into a tool of resistance.

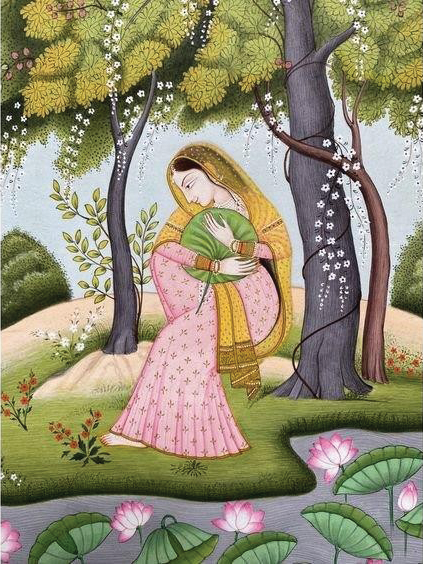

Similarly, in classical dance forms like Bharatanatyam, gender politics is deeply inscribed within performance traditions. The Rasas—are subtly gendered, with valor (Veera), anger (Raudra), and comic irony (Hasya) traditionally associated with masculinity, while devotion (Bhakti), compassion (Karuna), and love (Shringara) as shown in figure 2 are feminised. While Bharatanatyam originated in sacred temple traditions performed by Devadasis, its later Sanskritisation and male custodianship redefined its boundaries, confining female dancers to specific emotional registers. However, contemporary female performers have reclaimed Bharatanatyam as a space of agency—using the dance not only to embody traditional narratives but to subvert them, channelling rage, resilience, and autonomy into movements that defy rigid gender binaries.

Figure 2: Shringar Rasa: The Rasa of Love and Beauty

Source: Historified

Digital artist Aya Nakamura uses technology as a battleground, remixing traditional Japanese art with cyberpunk aesthetics to challenge gender norms in pop culture. “Digital art is my way of hacking patriarchy,” Nakamura states. “Online spaces are battlegrounds too, and I use them to disrupt the norm.” By integrating glitch aesthetics and hyper-stylised feminist avatars, Nakamura’s work dismantles the rigid expectations of femininity in anime, gaming, and virtual culture, proving that art as resistance is not confined to physical canvases.

Men’s constructions of grief are accompanied by narratives of heroism, intellectualism, or self-reliance. Women’s constructions of loneliness, however, are deeply personal, expressing vulnerability, social isolation, and the weight of enforced solitude. Feminist rage, once pathologised as hysteria or emotional excess, has been reconfigured in feminist art practice as a radical energy of creative insurrection. This power of transformation is evident in the work of feminist artist such as Kara Walker, whose silhouettes expose the grotesquerie of racial and gendered violence with confrontational force.

The Double Standard in Art and Cinema

The deeply rooted double standard of art and cinema is articulated in the androcentric assumption that male narratives are ipso facto universal, and female narratives remain on the periphery as “niche” or “women’s.” The gendered typology recreates a stratification of culture where male subjectivities become the norm, and women’s art finds itself relegated as subcultural deviances (Mulvey, 1975).In cinema, this asymmetry is particularly glaring- feature films with male protagonists are positioned as universally resonant, and the female-led films are weighed down by gendered qualifiers, reducing their apparent cultural gravitas. For instance, Queen (2014), a Hindi film directed by Vikas Bahl, was framed as a “women-centric” narrative rather than simply a coming-of-age odyssey, despite its themes of self-discovery being universally relatable. This linguistic and critical compartmentalisation perpetuates the notion that men’s stories articulate the human experience writ large, while women’s experiences remain ancillary, requiring explicit categorisation to justify their presence in mainstream discourse. This epistemic exclusion not only marginalises female artistry but also perpetuates a hegemonic cultural landscape wherein the male gaze dictates artistic legitimacy (Bell Hooks, 1992).

Case Study: Queer Liminality in Amruta Patil’s Kari

Figure 3: From Kari, Page 029

Source:RED INC.

Amruta Patil’s Kari (2008) unravels the existential weight of queerness, alienation, and urban estrangement through a protagonist who exists in perpetual in-betweenness. Kari, cast adrift after a failed double suicide, moves through Mumbai like a ghost—neither fully present nor entirely absent—her queerness rendered not through overt activism but through the city’s quiet, unrelenting hostility. Mumbai, often romanticised as a space of reinvention, becomes a suffocating entity, its rigid heteronormativity pressing against Kari’s spectral presence.

Visually, Patil subverts realism, distorting space and structure to mirror Kari’s fractured interiority. The novel’s silence—both in Kari’s stone-faced detachment and its sparse verbal exposition—turns absence into a narrative force. Kari’s androgyny, the jagged unpredictability of Patil’s linework, and the sprawling, claustrophobic cityscapes collectively resist categorisation, mirroring the protagonist’s own refusal to conform.

A Celebration, A Reckoning

Women’s art has never been mere decoration—it has always been rebellion. To create, in the face of erasure, is an act of defiance. To take up space, to refuse to be contained, to paint, to write, to dance, to perform—this is a revolution. And this revolution is unfinished. Even now, the battle continues. Women’s art is still asked to justify its presence, still measured against the universal standard of male experience. But perhaps universality itself is a myth, and the truest art is that which dares to speak in a voice unbowed. When women reclaim artistic space, they do more than create—they rewrite the very fabric of cultural memory, challenge stereotypes ensuring that the future will not look back and find them missing.

This International Women’s Day, we do not merely celebrate women in art—we bear witness to their endurance, their defiance, and their boundless creativity. We stand in the presence of centuries of unheard voices, now rising, now thundering, now refusing to be silenced ever again.

Leave a Reply